[93]

Marc-Adélard Tremblay (1922 - )

Anthropologue, retraité, Université Laval

“L'Anse des Lavallée:

An Acadian Community”.

Un chapitre publié dans l'ouvrage de Charles C. Hughes, Marc-Adélard Tremblay, Robert N. Rapoport et Alexander H. Leignton, People of Cove and Woodlot. Communities from the Viewpoint of Social Psychiatry. Vol. II. The Stirling County Study of Psychiatric Disorder & Sociocultural Environment, chapitre 3, pp. 93-164. New York : Basic Books, 1960, 574 pp. Un chapitre publié dans l'ouvrage de Charles C. Hughes, Marc-Adélard Tremblay, Robert N. Rapoport et Alexander H. Leignton, People of Cove and Woodlot. Communities from the Viewpoint of Social Psychiatry. Vol. II. The Stirling County Study of Psychiatric Disorder & Sociocultural Environment, chapitre 3, pp. 93-164. New York : Basic Books, 1960, 574 pp.

- Introduction

-

- I. POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

- II. SUBSISTENCE PATTERNS

- III. PATTERNS OF COMMUNITY LIFE

- IV. PATTERNS OF RELIGIOUS LIFE

- V. FAMILY LIFE PATTERNS

- VI. SENTIMENTS

- Nous sommes venus il y a trois cents ans, et nous sommes restés…

- Nous avions apporté d'outre-mer nos prières et nos chansons : elles sont toujours les mêmes. Nous avions apporté dans nos poitrines le cœur des hommes de notre pays, vaillant et vif, aussi prompt à la pitié qu'au rire, le cœur le plus humain de tous les cœurs humains.... [Toutes] les choses que nous avons apportées avec nous, notre culte, notre langue, nos vertus et jusqu'à nos faiblesses deviennent des choses sacrées, intangibles, et qui devront demeurer jusqu'à la fin.

- Autour de nous des étrangers sont venus, qu'il nous plaît d'appeler les barbares ; ils ont pris presque tout le pouvoir ; ils ont acquis presque tout l’argent.... Rien ne changera, parce que nous sommes un témoignage. De nous-mêmes et de nos destinées nous n'avons compris clairement que ce devoir-là : persister... nous maintenir... Et nous nous sommes maintenus, peut-être afin que dans plusieurs siècles encore le monde se tourne vers nous et dise : Ces gens sont d'une race qui ne sait pas mourir... Nous sommes un témoignage.

- Louis Hémon

Maria Chapdelaine

[94]

Introduction

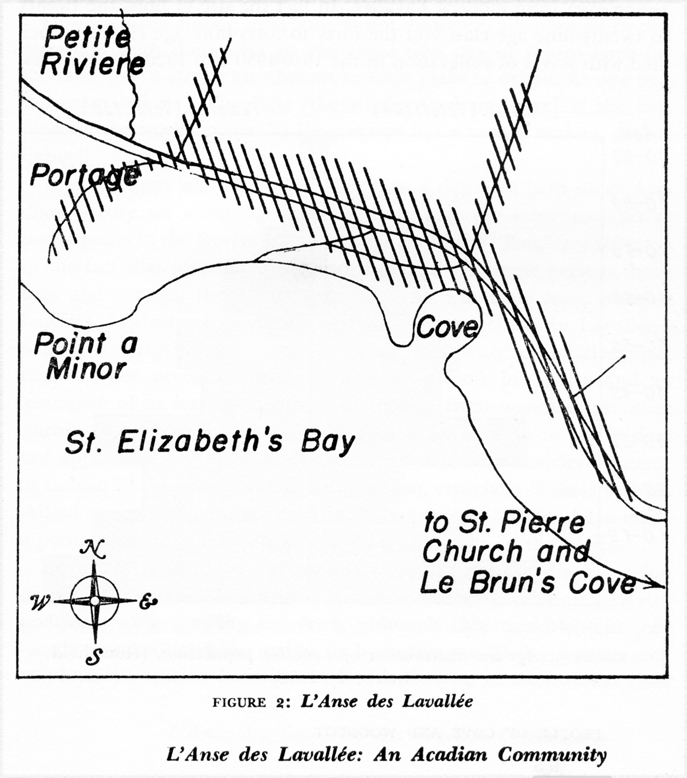

SEEN FROM ITS LANDWARD SIDE, the outlines of Lavallée's white houses stand sharply against the blue surface of St. Elizabeth's Bay, as they line the road for over a mile in the Municipality of St. Malo. Dominating the landscape from a hill on a cape nearby is St. Pierre, the parish church, with blunt, sturdy towers. Such features are typical of Acadian villages on the seaboard : a string of similar houses along the highway, near the sea, and a church tower standing not far away. Beyond these, however, there is something distinctive, although hard to define-perhaps it can be called an air of well-tended prosperity -which sets Lavallée off from many other Acadian villages.

The community contains almost 300 people living in some eighty households, and it is bounded with the bay on the south and the forest to the north. On the eastern side is another settlement, Le Brun's Cove ; the western edge is formed by a stream, the Petite Rivière, and by a portage, a patch of uninhabited land, grown wild in brush and woods. Still further to the west is Grande Marée, a smaller settlement.

Branching off from the main highway are several gravel roads, some leading northward to the forests of the interior and some southward to the shore. The backland roads, after a few hundred feet of houses and tended gardens, soon pass through fields grown into alders and small trees, and then to the woodlots which are part of Lavallée's most important economic resource.

The roads to the shore pass between marshy lowlands about one half mile in width which separate the houses from the Bay. Toward the center of the village, however, these lowlands are eclipsed by a thumb of the Bay that reaches to the highway, forming a cove. It is from this that the community takes the first part of its name, L'Anse des Lavallée. The places of business-stores, a hotel, sawmills, and post office-lie at the head of the cove. On the west side near a wharf are piled logs and cut timber belonging to one of the largest lumber companies in Stirling. On the other side of the cove is a cooperative sawmill and wood manufacturing plant making window frames and doors, the only one of its kind in the County.

The village has a history in which its Acadian residents take pride. One of the subdivisions, Minor Point, is considered the "cradle" of the Acadians today in St. Malo, and is revered by many others throughout the Atlantic Provinces and Eastern States, being a center of pilgrimage [95] on special occasions. As noted in Chapter I, some Acadians avoided the Dispersal of 1755 by flight. A group of about 120 are thought to have come from Port Royal and landed on what is now Minor Point. They spent the entire winter there and suffered greatly from exposure, malnutrition, and disease. Most of them died and were buried on the Point, and a chapel has since been erected in their memory. The survivors apparently managed better the second year and their number may have been augmented by others who had been hiding in the woods. At any rate, they were there to meet the larger group of Acadians who came to Stirling County in 1768 (see Chapter I, pp. 45-46).

FIGURE 2 :

L'Anse des Lavallée

Thus Lavallée's history as a community stretches back almost 200 years. The village has come through both severe pioneering hard [96] ships, and prosperous periods of commerce and lumbering to modern days of change and uncertainty in which the outside world forces itself increasingly upon this Acadian minority.

I. POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

The age and sex distribution of Lavallée shows some features which have important implications for community life. As seen in Figure 3, there are a few more females than males (152 total compared to 144), particularly in the younger age grades. The most noticeable feature of the distribution, however, is in the category from twenty to twenty-nine years, where there are almost twice as many females as males.

Such a distribution reflects, for one thing, heavy emigration among young men from modern Lavall6e. In fact the size of both the twenty to twenty‑nine age class and the forty to forty-nine age class is associated with waves of emigration in the 1940-1950 and 1920-1930 decades.

FIGURE 3 :

Age-sex distribution of Lavallée population,

(Household Inventory, 1952)

[97]

The patterns of migration from Lavallée are similar to those of most Acadian communities on the shoreline of St. Malo. As one might expect, emigration by youth is viewed in various ways by local leaders as well as by the relatives left behind. Some try to keep the young at home ; others feel that if they are to obtain suitable work and "better themselves" the young must migrate to urban centers or at least leave Stirling County. As a rule, people learn about job possibilities through family ties or friends who have already moved. It is rare for a person to strike out on his own to look for work in an area in which he has no previously established contacts. Another important factor bearing on migration is that young people nowadays receive more education than formerly and so come to believe they must move elsewhere to find opportunities commensurate with their training. This is part of a general rise in expectations with regard to standards of living.

Opinion even among the young is not, however, all oriented in one direction. Both those who go and those who stay or return have for the most part a strong attachment to their place of origin. As one person expressed it : "The Baie [the whole Acadian Shore] is the best place in the world to live, as long as one has a way to make a decent living."

The Acadians who return often express a desire to help other Acadians secure an advantageous education, and are sometimes active participants in the Revival. The feelings about the "Baie" are reflected in the fact that most migrants from Lavallée are single persons, both men and women ; there has been as yet no wholesale emigration of families. Against a background of comparative security in Lavallée with non-mortgaged ownership of house, assistance of relatives and friends when necessary, production of some food, low taxes, and an assurance of at least a modest cash income from woodlots or other sources-the uprooting of an entire family for a move to a city does not appear inviting to most. This may change with the development of industrial projects in the Atlantic region, especially if these call for skilled or semiskilled workers. Already one or two families have made a permanent move for such jobs, a thing unknown in the past.

In former times there was considerable difference in the migration of men and women. Twenty-five years ago, for instance, most girls did not leave to go looking for work, although they could obtain jobs locally as schoolteachers, maids, or housekeepers. Today women seek employment outside Lavallée, and with the rise in educational level [98] they are as well prepared as the men in some fields, particularly in white-collar occupations. Although such wider opportunities have had effects on the woman's place in the home and community, it is important to note that most women in Lavallée still conceive their fundamental role to be that of wife and mother. "Career girl" goals have as yet no influence in this community.

Also relevant to the migration patterns of Lavallée is a change in the form of land inheritance. In the past, land was divided by a father equally among all the male heirs. As a result, the portions threatened to become so small in time as to have very little value. Today, in order to obviate such a disaster, family property passes to only one heir who is expected to carry on the traditional occupation of the family, and this heir is not necessarily the eldest.

Questions concerning migration both of household heads and of their families were included in the FLS. In terms of indices constructed from these items, the bulk of Lavallée heads of households may be characterized as long-term, fairly stable residents of the community.

We assessed this by means of a "residence" index, in which we estimated the relative proportion of the respondent's life spent in the community of present residence. For a description of the building of this index, see Appendix B, p. 491. The distributions for Lavallée can be seen in Table III-1.

TABLE III-1.

Residence Index for Lavallée Household Heads (FLS)

|

Per Cent of Life Spent in Community

|

|

|

80-100

|

|

|

60-79

|

|

|

40-59

|

|

|

20-39

|

|

|

0-19

|

|

|

Total per cent

|

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

|

As can be seen, over half (54 per cent) of Lavallée heads of households have been in the community at least three fifths of their lifetime, and altogether 75 per cent have been in Lavallée for at least two fifths of their lives.

A second measure is a "recency" index, which assesses the length [99] of the respondent's most recent stay in the community, disregarding moves he might have made earlier.

TABLE III-2.

Recency Index for Lavallée Household Heads (FLS)

|

% of Household

Heads

|

|

Entire lifetime in present community

|

|

|

Last 20 years or more continuously in present community, but not entire lifetime (1932 or before)

|

|

|

Last 10-19 years continuous, but not last 20 (1933-1952)

|

|

|

Last 5-9 years continuous, but not last 10 (1943-1952)

|

|

|

Not in present community continuously for past

5 years (1947- )

|

|

|

Total per cent

|

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

|

Again we find that most of the population of household heads (62 per cent) tend to have been in Lavallée continuously for at least the last ten years, quite aside from where they may have spent other portions of their lives.

Turning to another demographic feature, marital status, about one third of the adults (those over twenty years) are unmarried. Some are advanced in years, being widowed or lifelong bachelors and spinsters ; but most of them are young. Perhaps indicative of a general trend toward later weddings than formerly (and later than other rural parts of Canada) is the fact that in the age class twenty to twenty‑nine years, twenty-one out of a total of thirty-one (65 per cent) are unmarried. Among these there are more males than females.

Of the seventy-eight households in Lavallée examined intensively by means of the Household Inventory (see Appendix F), the overwhelming proportion had a male as the chief of the household unit, seventy-one out of seventy-eight households, or 91 per cent. [1] This pattern somewhat contrasts with that in the Depressed Areas, as will be discussed in Chapter V. By "chief" we mean economic provider and (at least nominally) decision-maker. In Lavallée this position is especially reinforced by sentiments concerning proper male and female roles.

Another point to note is that the women tend to be more educated [100] than the men. This holds for all adult age classes, despite the fact that the range is greater for men, inasmuch as more of them have been to college. Almost 15 per cent of the male heads of households have had some university training, compared to 4 per cent of male household heads for the County as a whole. Although no women have been to a university, 88 per cent of them have completed from eight to twelve grades. The modal educational attainment of household heads, both male and female, based on the FLS, is the category eight to ten years. Data from the Household Inventory place the average grade of attainment for women in Lavallée at 9.0, while that for men is 7.5. This level of attainment is higher than that for other Acadian communities. Almost one fourth of the wives in Lavallée were schoolteachers before marriage (which was of course at a time when requirements for certification were less stringent than now) and their influence in encouraging education in the community has been strong.

The figures reflect only partially the educational attainments of Lavallée people, since an unknown proportion of the college graduates (e.g., priests, doctors, and other professionals) never returned as residents to the community after college and higher training.

The religious and ethnic characteristics of Lavallée were noted in Chapter II, where criteria and indices for selection of the community as a relatively integrated area were presented. It will be recalled that all people in the village are at least nominally Roman Catholics, most of them devoutly so, and that over 90 per cent are of "pure" Acadian ancestry.

II. SUBSISTENCE PATTERNS

Lumber has always been the most important source of cash in Laval1ée, the means by which goods and services are purchased and taxes paid. For those who own lots, lumber also provides a "bank account", a combination of investment and savings for use in times of adversity. Approximately 25 per cent of the family heads own large woodlots, and this in some ways marks these people off as a special economic class. The rest, however, still have lumbering as the most important single economic resource; for many own small woodlots, or work for wages on someone else's land.

[101]

Other economic activities contribute only in an ancillary manner. Farming, for instance, while it tends to be secondary in most of the County, is even less important in Lavallée. About twenty households grow their own vegetables, and a few keep cows, a pig, and some chickens. But even to these people such work is only part time, done after hours in lumbering or wage‑labor in some other job.

Although some Acadian communities fish the waters of St. Elizabeth's Bay, Lavallée does so only to a very small degree. Geographic features may play a part in the lack of this activity, since Lavallée's long tidal flats do not allow an easy landing of boats at low water. For pleasure, on the other hand, people dig clams during the spring tides at nearby Grande Marée, where "grosses coques" (quahogs) are found. These unusually large clams are considered a delicacy and often are used in an Acadian dish made of grated potatoes strained of their water content, pâté à la râpure.

Hunting is another subsistence activity in which the pleasure of doing it is the main feature. As in all St. Malo communities, deer hunting in the fall is very popular among men. Since the woods are within everyone's reach, the hunters come from all parts of the economic scale. Most Lavallée men go deer hunting at least once a year and some people go as often as twice or three times a week during the open season. Wealthy hunters may organize camping parties with guides and go inland to the more inaccessible woods and barrens. Whether or not a trip is marked with successful kills, there usually is celebration and good times, in some cases with heavy drinking. This latter aspect of the deer season is perhaps in the process of becoming as important as the hunting itself.

The size and quality of the original timber holdings of the settlers, and the particular historical circumstances which facilitated maintaining these in local hands, lie behind Lavallée's relative prosperity and security today. In the 1880's, a number of English lumber corporations began cutting in St. Malo. From small and large woodland owners they bought all the lots they could get, and moved up toward Lavallée from the western (most distant) end of the Municipality. Because lumbering at the time was subject to the demands of the spring river drive, there was concentration on the lands immediately surrounding river systems. The companies jumped from river to river in their march through the municipality. To the west of Lavallée, lots were successsively [102] cut to the ground as the woodlands were bought from the Acadians who were willing to sell at the time (in large measure due to the depression that occurred during the latter part of the nineteenth century). According to older informants, the companies ruined and exhausted much of the finest timber land in this part of the Province.

But the corporations' ambition to cut all of St. Malo's woodland never materialized, for one company after another went bankrupt. The last wave of woodlot purchase faltered just at the neighboring village of Grande Mar&, and Lavallée was spared. One lumber dealer told us :

- Our prosperity is a historical accident. Lumber companies never reached our community. Lavallée Acadians cannot explain their prosperity by the foresight of the ancestors. Our fathers never sold their land because they were never offered a deal. That was our luck.

Whatever may have been the case of foresight at the time, in the last two or three decades woodlot owners have become sensitized to the need for conservation in order to have a sustained forest yield. Consequently, the community's main resource is now cut in such a manner as to keep it productive. Thus Lavallée's current circumstances do, we think, have a component of both foresight and care.

The outstanding characteristic of the businesses in the community is their familistic nature. Of the dozen or so, nine are organized along family lines. In the sawmilling industry alone, there are three family-owned and family-staffed corporations. One sawmill is in the hands of two brothers and three first cousins ; another is owned by four first cousins ; and the third is owned and managed by two brothers and a cousin. Another sawmill, although not in the same sense a family business, is a partnership of affinal relatives, two brothers-in-law.

The most important lumber company (having woodlots of its own, a general store, and a lumber dealing business, though no sawmill) is owned by two brothers and a first cousin. A father and son jointly own a garage ; two brothers are the proprietors of a dry cleaning concern ; a fishing boat (this was a short-[term business venture) is owned by two cousins ; and, finally, the village's tourist cabins belong to a mother and her three sons.

In general, one can say that if a business concern embodies Partners, they are relatives. Moreover, there are only a few enterprises which [103] are not organized on a partnership pattern and these tend, except for the cooperative, to be minor. One exception to this is a fish plant which, although located at nearby Le Brun's Cove, is owned by a Lavallée resident. Kinship bonds, therefore, extend far beyond the social activities of the family and penetrate the economic structure of the community.

Reflections in economics of primary group feeling other than kinship are found in a Credit Union which the community has had for a number of years, organized on a parochial basis. In 1948, when a local sawmill closed, the Credit Union voted to buy the business and operate it on a cooperative basis. Although the vote by the directors of the Union was unanimous and the Cooperative was welcomed by wageworkers and smaller woodlot owners, it was opposed by some of the families in control of the sawmills and lumber companies. Despite this, the Cooperative survived and became successful, greatly aided by the parish priest.

Today, the smaller woodlot owners continue to support it strongly, because they are able to get a relatively larger share of the proceeds from the sale of their logs. The Union has two departments, one mainly concerned with making boxes for the fish plants, and the other with producing windows, doors, staircases, and similar items needed for house construction. The objectives of the organization have been expressed by one of its presidents :

- The main goal of the Co-op is not to make profits, but to provide job opportunities for families of the parish and to improve standards of living, in this way counteracting the reasons for migration to industrial centers. The Co-op is thinking of production. This would certainly stabilize the industry and may insure its survival.

Having sketched this background of economic activity, we can now turn to the individual worker. But to draw the occupational profile of Lavallée requires some preparatory comment. As in the County as a whole, occupational versatility is an important feature, and figures with regard to "main" occupation must be evaluated against secondary and tertiary jobs and against other contributions to the total subsistence, such as part‑time farming. With this in mind the occupational distribution for "main" job of male household heads (that which contributed most money for the five years preceding the FLS in 1952) is presented in Table III-3.2 [2].

[104]

TABLE III-3.

Types of Main Occupations of Main Earners in Households in Lavallée (FLS)

(excluding those out of the labor force for five years or more)

|

Type of occupation

|

|

|

Owner and salaried

|

|

|

Own account in agriculture

|

|

|

Own account in fishing

|

|

|

Wagework in more secure industries such as railroad and water transportation, government service, etc.

|

|

|

Wagework in construction

|

|

|

Wagework in truck transportation

|

|

|

Own account in forestry

|

|

|

Wagework in primary industries

|

|

|

Wagework in fish canning and curing

|

|

|

Wagework in wood products

|

|

|

Total per cent

|

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

|

Further details of the above categories will be found in Appendix B, pp. 452-454. In regard to the above and the following index, the "household head" referred to is in all cases the "main earner" in the household, even though the respondent may actually have been the female household head under the rules of alternate sampling by which the questionnaire was administered. In Table III-3 we may note that over two fifths of such main earner household heads in Lavallée are found in the first category, "owner and salaried," comprised mostly of large woodlot owners who employ workers to cut for them.

The rest of the "owner and salaried" category is taken up with entrepreneurs and people in various managerial and white‑collar capacities. The smaller woodlot owners are mostly in the category of "own account in forestry," while a few occur in wage jobs of various types, from which they receive the bulk of their steady cash income.

Almost one half of the household heads in Lavallée have secondary occupations. [3] The majority of these people are in the semiskilled, blue-collar group and it is rather unusual for a person in the owner and salaried category to have a second job of any importance. All in all, the modal occupational position is entrepreneurial or salaried and for the most part it involves large or small woodlot owners who are primarily dependent upon the cutting and selling of logs. The rest [105] of the household heads take a variety of jobs to fill out their income.

In Lavallée today-as in the past-it is considered commendable to master a number of skills. In former times, when there was more or less regularly a shift of occupation with the seasons, this was more easily achieved then now. Some kinds of positions, moreover, such as the professional, the proprietor or the manager, do not involve any major change in activity with the cycles of the year, being removed from such a primary relationship to nature. Wageworkers, on the other hand, are still subject to seasonal shifts and hence they need supplementary work at various times during the year. Many independent farmer-lumbermen also work for wages when they have a chance, such as on road repairs or construction jobs. Employees in the Cooperative and other sawmills likewise work there only a part of the year. For them winter is the season of being laid off, and for about four months most draw unemployment compensation.

Survey data further illuminate this picture. Seventy-four per cent of the main earners in the household were employed continuously over the twelve-month period preceding the survey ; and among the unemployed, very few were idle for as long as six months (see Table III-4).

TABLE III-4.

Degree of Unemployment of Main Earners of Households in Lavallée (FLS)

(excluding those out of the labor force for five years or more)

|

|

|

|

Not without earned income at any time during the twelve months preceding survey

|

|

|

Without earned income for three months or less during this time

|

|

|

Without earned income for from four to six months

|

|

|

Without earned income for seven months or more

|

|

|

Total per cent

|

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

|

It should be recognized that in Table III-4 "earned income" does not include savings ; hence, it is possible for a man to be without work but still have money available, which does happen in Lavallée. For the County as a whole, it will be recalled, the relative proportion of household heads employed during the year preceding the survey was 68 per cent ; the proportion who were unemployed for seven months [106] or more was 6 per cent. The proportion employed in Lavallée is therefore slightly higher than the County averages.

A point of interest emerges when occupational distribution is considered in relation to age. We find that there is a tendency for older people to be in lumbering (an extractive industry), whereas younger people tend to be in the service, or in the unskilled, wage-labor group. This seems indicative of the larger process of social and cultural change-the young prefer to work for wages, sometimes away from the community, rather than depend upon lumber and subsistence farming at home. Lavallée, like other small rural communities in Stirling, was organized around the extractive industries, but today it seems to be shifting-despite its fundamental base in lumber-to a manufacturing and service type of economy and occupational pattern. In addition to sheer preference on the part of the young men for a different type of work, this pattern might be attributable to greater efficiency, thus reducing labor needs, in the extractive processes themselves.

As we noted in our discussion of the selection of Focus Areas (see pp. 66, 71, 72), Lavallée is among the wealthiest communities in the County, and is, undoubtedly, the richest along the Acadian shore. The distribution of wealth, however, is uneven, with about half a dozen nuclear families having assets that may run to $100,000 each, and it is this which raises the over-all community average. The other nuclear families, however, must not be considered as isolated and unaffected by this wealth. On the contrary, due to the extended kinship system and the accompanying sentiments of obligation, economic security is spread widely throughout the community.

The wealthy families aside, most workers in the village have, according to key informants, an income that is about average for the County-from $2500 to $3000. This figure may seem low by urban standards, but it is actually higher than might first appear, if one considers it in the Lavallée context. The security, especially in sudden emergency, that is provided by the kinship system has already been mentioned. To this should be added low taxes, mortgage-free houses (most of which are large-the average number of rooms is eight-and well kept), the materials and skills to do one's own maintenance, the opportunity to grow a considerable part of one's own food, the chance to cut one's own wood for heating, and numerous other items which are in effect hidden income or at least would have to be regarded as such if a comparison were to be made with urban salaries.

[107]

TABLE III-5.

Scale of House-type and Household Possessions in Lavallée (FLS)

|

|

Rated Quality of Furnishings

|

|

|

|

Two or More Rooms per Person

|

Washing Machine or Laundry Sent Out

|

Rated Quality of Size, Roofing, Walls and Foundation, Yards, and Outbuildings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

|

Note : In the above table (and others of this type) a “ + ” indicates that the given characteristic is present and a “ - ” means that it is absent. In the case of a continuous quality, such as relative affluence of furnishings, “ + ” and “ - ” indicate a rating, respectively, of above and below a particular cutting point with respect to the item. See Appendix B, pp. 461-462.

A reflection of Lavallée's advantaged economic position can be seen in the main types of material possessions. A composite scale made of various ratings of house type and condition, and the presence or absence of certain appliances and conveniences, points up its high standing (see Table III-5). For a discussion of the building of this scale, see Appendix B, p. 460 ff. As noted before, this scale entered as one component [108] in the "Index of Material Style of Life" mentioned in Chapter 1.

Noting some of the items in Table III-5, we find that about one quarter of the homes in Lavallée have good quality, well cared for furnishings ; furnace heating ; a refrigerator ; flush toilet facilities ; two or more rooms per person ; a washing machine or laundry service ; a large, well cared for house and grounds ; and electricity. As in a scale of this type, the proportion of people having all the items of material goods mentioned decreases as the total number of items itself increases. Thus, we find at the other end of the scale, 97 per cent of the Lavallée houses are rated favorably on house-type and quality, and, in addition, have electricity. All houses have at least electricity. Both to the person driving through and to the long-term resident, Lavallée's outward appearance is indeed one of prosperity.

Comparing the averages for the County as a whole (see Appendix B, Table B-9), only 5 per cent of the FLS respondents have all the items named, in contrast to the 23 per cent for Lavallée ; and only 75 per cent have homes rated as large, spacious, and well cared for, with electricity and adequate laundry facilities, compared to Lavallée's 97 per cent ; 96 per cent have electricity, where Lavallée has 100 per cent. For the County as a whole, the modal collection of material possessions according to this scale is that of having electricity ; an "average" or better rating on the quality of house-type and outbuildings ; a washing machine or laundry service ; and two or more rooms per person. Lavallée's. modal pattern is that of having all eight of the material features composing the scale.

Two other indicators which bear on the economic position of Lavallée are ownership of automobiles and the carrying of life insurance. Thirty-three per cent of the household heads in Lavallée both own automobiles (65 per cent owning a 1950 model or better) and carry life insurance. Thirty-eight per cent have one or the other of these financial assets ; and only 29 per cent have neither. This compares to 21 per cent in the County as a whole having both ; 34 per cent having either ; and almost half, 45 per cent, having neither.

All these factors-job stability and relatively steady income, standard of living, material possessions‑bespeak the same qualities in Lavallée : relative economic prosperity and security.

[109]

III. PATTERNS OF COMMUNITY LIFE

One of the strongest impressions we derived is that everyone in Lavallée feels he can count on relatives and neighbors to help in any emergency and that he will in turn go to great lengths to give such a service. There is, in short, marked community sentiment, and it exists not only in words but also, as we discovered, in action.

In the FLS survey one question asked what people thought would happen if their house burned down-could they expect help from their whole community ; only from neighbors and immediate family ; or from no one else except themselves ? Eighty-one per cent of the household heads in Lavallée said they thought the entire community would pitch in to help. Several years after the survey a house did burn down and the community did in fact contribute extensive assistance in one way or another, some helping to construct a new house, and some collecting money to aid the family in re-establishing itself.

To the same survey question, 54 per cent in the County as a whole, 25 per cent in Fairhaven, and 31 per cent in the Depressed Areas answered that they thought the whole community would help. Thus, relatively more people in both the County and the other Focus Areas thought they would have to rely on themselves in such an emergency. There were, however, no accidents of a nature to test these expectations in the other Focus Areas.

Visiting patterns constitute another expression of community sentiment. It is the custom to enter a house through the kitchen door without knocking. Women may go up the road during the day to a relative's or friend's house for chatting, discussing babies, food, or people ; and among the men, many have jobs which allow them to drop in to the general store or the post office and spend time discussing lumber prices, the hunting season, politics, and, of course, personal events and community life. Sometimes a family as a group will visit another family in the evening, either for some form of recreation such as a game of cards, or just for conversation. At the time of the field study, television had not yet come into the village.

There are some differences in visiting patterns according to economic status. The well-to-do families tend to keep more to themselves ; there appears, in fact, to be a general restriction in relationships by these families and less of the informal visiting, even between relatives with approximately the same economic resources. Many seem too preoccupied [110] with business problems. Others tend to do their social visiting mainly with people of the same general socioeconomic level in other communities along the shore.

Nevertheless, a neighbor is considered to be a person whom one lives near and visits and also a person from whom one expects immediate and unstinting help in the small as well as the larger needs of life. For instance, if only one house out of several in a neighborhood has a telephone, all people living nearby will feel free to make and receive calls there. Further, in case of trouble, a neighbor is usually the first to be asked, and he would feel slighted and annoyed if he were not.

The person who does not share in the life of his neighborhood and does not mingle socially with those living nearby is considered deviant, the one whose actions are to be explained. When such isolation does take place, moreover, it is generally because an individual is being deliberately ostracized for having transgressed some strongly held value-sentiment. But such treatment occurs rarely and only as a response to extreme acts, such as marrying outside the Church and then bringing the spouse to live in the community.

When one sees families visiting each other in the evening, one pattern is apparent which symbolizes much of the rest of community life. This is the division between men’s and women's roles. Although there has been some change in recent years-especially among the women from the more well-to-do and better educated families-the world of men and the world of women remain markedly different. As is often seen elsewhere, women usually gather together in one corner of the room, discussing matters that are of primary interest to them, while the men do the same thing in another part of the room. In Lavallée, however, there are strong sentiments in support of this behavior based on the religious philosophy of the Roman Catholic Church, with its emphasis upon the mother and the home as transmitting the faith, and upon the man as provider.

Of the several factors entering into neighborhood and community cohesion, ethnic homogeneity is undoubtedly one of the most important. This has both its historical roots and its modem aspects. As noted earlier, Lavallée includes what is considered the original settling place for Acadians in the County. A monument to the memory of the first settlers stands at the edge of the village, serving as a reminder of their history as a "martyred people." The precipitates of this history [111] exist today in the general culture of the community, with its language, religion, family sentiments, and numerous minor-but characteristic-traits such as the pâté à la râpure. Everybody except one "war bride" who came into the village upon marriage speaks the Acadian dialect. Nearly all speak English also, with varying degrees of fluency. French as a written language, however, is much less widely used, and this applies not only in Lavallée but also in St. Malo as a whole.

A mark of ethnic ingroup feeling in Lavallée is the fact that some of the important leaders in the Acadian Revival movement of St. Malo are residents of this community. The Revival (see pp. 40-41), is directed at the re-establishing of Acadian influence over the entire Maritime region through population spread, increased attention to the background of Acadian history and culture, use of oral and written French, growth of a political climate favorable to the Acadians, and their increased importance in the church hierarchy. Most of the heads of the more influential families strongly support this movement, although some of the business leaders fear that too much emphasis on Acadian separateness may alienate their English business contacts. Such hesitancy is not voiced much in public.

Some of the sentiments bearing on the Acadian Revival are illustrated in certain of the survey indices. Table III-6 reports on a scale of in-group commitment among the Acadians of Lavallée. For dis-

TABLE III-6.

Scale of In-group Commitment Among Associated

Acadian Household Heads in Lavallée (FLS)

|

Response Patterns

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

%

|

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

36

|

|

-

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

34

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+

|

30

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Total per cent

|

100

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

(33)

|

Key to columns :

1 : has reservations about mixing socially with the English.

2 : would censure or try to persuade back a friend who left the church.

3 : would object strongly to a child marrying a non-Catholic.

4 : married to a Catholic.

[112]

cussion of this index, see Appendix B, p. 473 ff., especially Tables B-20 and B-21.

All household heads in the survey of Lavallée are married to Roman Catholics and would object strongly to one of their children marrying a non-Catholic. Seventy per cent have these characteristics and, in addition, would censure a friend who left the church and try to reconvert him. Thirty-six per cent have all the above plus reservations about mixing socially with the English.

For associated Acadians in St. Malo, excluding Lavallée, the corresponding figures are 90 per cent and 31 per cent. This suggests that Lavallée has some tendency to emphasize these sentiments a little more than most Acadians do.

Despite the marked ethnic cohesion in Lavallée and pervasive sentiments supporting the idea of equality among all Acadians, there is, as already indicated, a division into social "prestige" segments more or less roughly defined according to a number of criteria. These segments are recognized by both the "high" and the "low" in the community, and their existence, though muted and even openly denied, is a social reality.

In this emerging "class system" of Lavallée, wealth and education weigh heavily in making for differentiation. But "respectability" and religiousness are qualifying criteria, and they enter the picture at crucially important points. The poor and uneducated, for instance, even though they may be highly religious and respectable, do not have upper status in the village, although they can have the middle range of prestige. Membership in the uppermost levels is given to the wealthy or highly educated who are also of irreproachable morals (at least publicly). Members of what may be roughly defined as "middle" levels are those "respectable" people with average or below average economic standing and educational achievement. This group forms the greatest bulk of the population, with fifty out of seventy-eight families being considered as belonging to it. The lowest (and smallest) group of people consists in those who are for the most part poor and "have a dark spot in their history," either because they have not fulfilled all their religious obligations or because they have committed minor offenses which are common knowledge (e.g., theft, sexual promiscuity, excessive drinking). They are, in fact, a "class of people" whom the rest of the Lavallée residents would like to see move out of the community.

[113]

It should be emphasized again that the system of social differentiation in Lavallée is neither crystallized nor well defined and hence cannot be properly compared with most of the class systems that have been developed by social scientists. [4] Nevertheless, against the background of traditional Acadian sentiments, by which the model for prestige ranking might be said to be the "exalted common man," this is something new and is one of the several features marking Lavallée off from the rest of St. Malo. It is as if, malgré eux-mêmes, they have formed a system of social differentiation based on wealth, education, and general overt adherence to their value‑sentiments.

As might be expected, if we contrast a rough "upper" and "lower" group according to occupation, most families of the higher level cluster in the proprietorial and managerial occupations, and most families of the lower category are in unskilled activities. Families of the middle group, however, spread themselves over the whole occupational range.

Some of the criteria of status position may now be illustrated in more concrete terms. If a family "gives" a son to the priesthood, this will bring extremely high prestige, no matter what its condition with regard to other criteria. But educational attainment (which requires a greater interest in community affairs, according to sentiments held by Lavallée people) and personally-achieved material wealth are also extremely important. Further, if wealth or education has been gained by an individual, some of the consequent prestige extends to other family members, as if to acknowledge that his success has been possible only through collective encouragement and support. Thus, through financial sacrifices and denials, a family might send a child to college and if he "turned out well" his higher status would be shared by those who took an active part in helping him. We often noted an expression of this "disseminated" prestige when a member of the community was being introduced. The point of reference was always in terms of kinship, but among the kin the person selected for reference was always one with high prestige : "This is Father X's brother. " "This is the father of Dr. Y." Sometimes the name of the individual would be omitted entirely in such introductions and he would be made known to the outsider only by his distinguished relative.

There is virtually no social interaction between the families of the upper prestige level and those of the lowest. As mentioned earlier, the behavior of the upper group includes less visiting with other people in the community and more association with high status persons outside. [114] The expensive quality of their entertainment and leisure activities fosters exclusion. Aside from this, however, people of the middle levels seem able to gain admittance only through the sponsorship of someone who is already a member, and there is a certain note of envy and jealousy. It seems evident that the sentiments of social equality are in some ways flouted by the expensive cars, travel, summer cottages, parties, and display which the upper people can afford.

Drinking as a form of leisure activity is widespread among both the highest and the lowest groups, with the middle being relatively temperate. The latter tend to use liquor only on special occasions, such as birthdays, weddings, and holidays. Family heads of the lowest prestige group drink more often than do the richer people, but less frequently in their homes, and so they are more often seen drunk in public. The latter is very unusual for a person of the upper level. Despite this use of alcohol, heavy drinking-lots of it, regularly-is generally condemned regardless of prestige position. It is especially criticized in cases where it interferes with work, child rearing, or family life. In extreme cases there may be intervention through organized action by relatives, neighbors, a priest, or doctor.

People in Lavallée as a whole now spend much more time in recreation than they did in the past when the hardships of making a living gave little opportunity for leisure. Moreover, not much distinction was made formerly between leisure, work, and other aspects of life, since many enjoyed activities centered in the family and church and there was pleasure in the shifts of occupation that came as part of the annual cycle. The change, for instance, from the spring river drive of logs to summer farming was one such shift. Leisure as a form of "relaxation" per se, however, was an alien idea-one without justification. Many of the older people in the community have never in their lives had a vacation.

For the younger people, however, leisure and vacation have considerable meaning, and this is part of the larger picture of socio-cultural change. The trend has been away from family-centered and work-connected recreation toward commercialized entertainment. A young informant speaks in this way about changes he has experienced :

- Some fifteen years ago, there were a number of young people in the community and we used to get together every week. We used to go to each other's home, play cards, sing songs, and dance. In [115] those days there were only a few cars around, and there were movies once or twice a year. We used to spend a lot of time at home, rather than traveling around or going to a movie.

The development of transportation has been much involved in the shift. The paved highway, the automobile, and particularly a shorter working day and week have made possible shopping in more urban centers such as Plymouth, Bristol, or even the Provincial capital ; roller skating at Grande Rivière ; playing pool and bowling at St. Pierre ; or vacationing at a tourist resort. With the exception of the last, none of these activities is carried out on a family basis.

As with forms of recreation so also with voluntary associations in Lavallée : there has been a growth in importance of institutions which extend beyond the boundaries of the community and are not family centered. There are no formal associations limited in membership to Lavallée people only, and participation in parochial, Municipal, County, and Provincial organizations is high-probably higher than in any other village along the Acadian shore. Lavallée has produced a large number of leaders active in such associations as the Board of Trade, the Association for the Education of Acadians, the Cooperative Movement, and the Liberal Association of St. Malo. Some 67 per cent of the family heads belong to at least one formal association besides the church, and 10 per cent belong to six or more. On the average, they belong to two associations.

As one might expect from knowledge of other areas, there are occupational and sexual differences in the patterns of membership. Those who do not participate in formal associations are found mainly among the unskilled and the retired, while the active joiners are among the professionals, businessmen, and people in other white-collar categories. Women more than the men join religious and educational associations, and men participate more in the economic, political, and professional groups. Both sexes are found in the social-recreational associations, though men predominate.

In the business field, there are two parish-wide and one municipality-wide associations which draw members from Lavallée. Two of these, the St. Pierre Credit Union (having about thirty-five to forty families from Lavallée as members) and the Lavallée cooperative, have already been discussed. The municipality-wide organization is the St. Malo Board of Trade, which has about fifteen Lavallée families represented. [116] its aim is to bring new industries into the region, promote tourism, stabilize employment, and achieve generally higher levels of living.

There are no unions in the community, and a movement in this direction has been strongly opposed by Lavallée business leaders. We may note also that there are no formal associations operating exclusively with a recreational aim in the community, although two outside associations of this type draw some men from Lavallée. These are the Latourelle Men's Club, serving the purpose of maintaining a bar ; and the Bristol Town Curling Club, which has a similar facility although its main purpose is, of course, recreation. The meaning of these two clubs will be evident when it is understood that the Province on the whole is "dry" and that no public bars or cocktail lounges are allowed in Stirling County.

Associations linked with formal education flourish in St. Malo and Lavallée residents play key roles in them. The community has its own branch of the Home and School Association (corresponding to the Parent Teachers Association in the United States), has members in the Association of Acadian Teachers and in the Association for the Education of Acadians. The latter association was organized recently in the Province and is, undoubtedly, the most important of all educational groups in St. Malo. It has multiple aims, among which are the increasing of levels of education, promoting "Acadian rights" in the school system and in the legislative procedures of the Province, opposing influences which they feel weaken Acadian consciousness of themselves, and promoting greater participation in the affairs and endeavors of other French groups in the nation. Six people from Lavallée belong to this association, and most of them hold leadership positions. Another association connected with education is composed of alumni of the Acadian college of St. Jean-Eudes, located in the parish next to Lavallée. This group was formed some fifty years ago and the members are spread throughout the Canadian Provinces and the eastern United States. The aims are similar to those of alumni associations everywhere : support of the alma mater and enhancement of its prestige.

Another aspect of the propensity for Lavallée people to join associations can be seen in political activity. Recently (1951), under the leadership of two community members, a group in the Municipality was revived to help guide and direct policies of one of the political parties of the Province. We may note that the member of the Municipal [117] Council representing the district of which Lavallée is a part comes from that community. The war veterans' organization, Canadian Legion, has four members in Lavallée.

In addition to membership in secular associations, the people of Lavallée are of course active supporters of church-sponsored groups. There are, for instance, three parish-wide, church-centered associations with representation in the village. These consist in the Holy Name Society, the Catholic Women's League, and the Choir. The first two are the most important religious associations in the parish. Lavallée people play leading roles in these and have greater participation than do people in Le Brun's Cove, St. Pierre, Frontière, and Philip's Point -communities which, with Lavallée, form the St. Pierre Parish.

The Holy Name Society, an association for men, was established in the spring of 1952. Its purpose is to promote frequent confessions and communions among the laity, each member pledging himself to receive communion at least once a month. It has as members about twenty household heads. Although the members are drawn from all classes and age levels, middle class and older men predominate. At first the society did not receive full support from the Lavallée residents because of its identification with Irish clergy and because of a dispute in progress at the time between the Irish and the Acadians. The society finally received active backing when the parish priest strongly urged its support.

The Catholic Women's League, to which some thirty Lavallée women belong, is an organization for married women (overlapping in great measure with the Lavallée membership in the Home and School Association). A few years before our study it was established in the St. Pierre Parish to replace another association, the Women's Institute. The latter group, with more secular aims and no affiliation with the church, was disappearing, and the Catholic Women's League stepped in. Members are expected to take an active part in preparations for the annual church fair, raise funds for parochial organizations, participate in the Home and School Association, visit the sick in the community, help the poor, and recite special prayers for them. The association meets regularly once a month.

The choir is responsible for singing at religious services (high mass, funerals, vespers, weddings, special services) and is strongly supported in Lavallée. At least ten of its approximately twenty members come from the village. It is of interest that there are no religious associations [118] specifically for unmarried boys or girls. Some, however, sing in the choir.

Education in Lavallée is highly valued, as can be seen in the membership of associations formed to promote educational facilities. Several historical factors would appear to be important in the development of this characteristic. One of these has to do with experience of the residents when they worked in L'Anse in a shipyard owned by an English family during the 1860's and 1870's. The unskilled Acadian laborers who saw clerks and office workers receiving higher wages became impressed with the value of education at that time and strongly encouraged their children to acquire it. This interest in schooling helped to contribute to the creation of the Acadian college of St. Jean-Eudes in Latourelle during the last decade of the nineteenth century. The college, the work of a missionary order, was built a few miles from Lavallée and dedicated to the memory of one of the great missionary priests of eastern Canada who had in the early nineteenth century pioneered the development of education among the Acadians.

Because the college is set up on the French-Canadian model of a "cours classique," the curriculum corresponds not only to the four college years in the United States but also to teaching from grade seven upwards. Some Lavallée residents have attended the college for a few years without doing what would be considered college work in English-speaking North America, yet this exposure to the atmosphere and perspectives of higher education is considered to fit them for positions of leadership. They are expected to take a prominent part in activities of the community and parish because it is said, "they are educated."

Learning, then, plays an important part in the definition and exercise of leadership in the community. But other factors are also important in selecting a man for leadership. General knowledge and experience ; wealth ; enthusiasm for the task ; vigor or evidence of arduous work toward goals of the group will also help define a person for the role. Probably the most consistent basis for leadership is education and experience in a particularly valued activity. Sheer economic power does not, of itself, seem to qualify a person. There is no exclusive leadership "stratum" in the community, and people from the middle as well as from the uppermost level have the opportunity to be leaders in one domain or another.

As noted earlier, there are no associations limited exclusively to Lavallée-an important fact in itself bearing on the wider group sentiments [119] of the Acadians-but the residents provide most of the leadership for associations of the parish as a whole, such as the Credit Union, the Cooperative, the Catholic Women's League, the Home and School Association, and the Holy Name Society. In 1952, for example, the presidents and most other officers of these associations were from Lavallée. Indeed, the only important person in these groups who came from outside the community was the parish priest.

With the mention of the priest, we come to an institution which, by its very nature, provides overarching leadership and guidance that are very effective in channeling socio-cultural processes in the community. The Roman Catholic Church hierarchy and Acadian tradition give the parish priest authority in widely defined religious aspects of life, with effective sanctions to ensure conformity. As one Acadian said to us : "When Father Lebrun is in the pulpit, people listen to him earnestly no matter if what he says is pleasing or displeasing. He has the duty and the authority to preach, and people have to listen to him."

Beyond the authority given the priest in matters pertaining to the religion, he also has influence in matters of education and recreation. But his power in such matters is more dependent upon his individual characteristics and personality than upon any clearly defined aspect of his priestly role. Therefore, in many ways the over-all strength of a parish's institutions depends upon the energy of its priest, even within the areas of influence formally ascribed to him. Lavallée's priest, a graduate from St. Jean-Eudes College, is probably the most active of all the parish priests along the Acadian shore. Among his achievements in leadership are the completion of the St. Pierre Church and rectory (which had been begun some thirty years before by a predecessor), the establishment of the Credit Union, and the organization of the cooperative.

Although the priest is a central figure in the control of socially deviant behavior in Lavallée, his activities are part of the larger pattern of informal social control over transgressions against shared value-sentiments. Socially disruptive behavior does of course occur and reprehensible actions do take place, but as a rule people try to settle these within the community itself through persuasion, precept, interpersonal influence, and social exclusion. Only if the matter is extensive, and if they are unsuccessful by these means will they take it to the police. The latter consist in the constables who, though rarely used, are still appointed for each of the subdivisions of the Municipality, [120] and the federal organization, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which maintains a detachment in St. Malo.

In a community such as Lavallée delinquency and deviancy are most generally defined as the public breaking of the moral precepts of the Roman Catholic Church. Through observation and intensive interviewing on this subject, we were able to gather information on the types and frequency of delinquent practices among adults over a twenty-five year period. None of these acts had been brought to the attention of the police, and we could find no evidence of a serious crime. [5]

Most transgressions had to do with sex, both adultery and premarital intercourse. It would seem that very few people currently practice extramarital relations ; and when they do and it becomes known, it is severely condemned. An element in these sentiments is the feeling that such behavior is a threat to the integrity of the family.

Feeling is not so strong with regard to premarital relations, yet Lavallée appears to be among the communities of St. Malo with the lowest prevalence. Altogether there are some fifteen married couples out of a total of about eighty who are reputed to have had sexual intercourse prior to their marriage. This is, of course, a clear violation of sentiments concerning chastity, and although it has been forgiven by the public at large and the couples are now socially accepted, it is still remembered, in some instances as long as thirty years afterward.

Another and much more lightly regarded type of deviant behavior is the breaking of the laws regarding alcohol. Liquor is supposed to be sold only through government licensed and controlled stores, for consumption in private. Consequently, breaking the liquor laws means making, selling, or buying liquor from sources other than the government store and drinking in public places. Transgressing community sentiments means taking excessive quantities or drinking on wrong occasions and getting drunk. During our study only one man in the community was apparently selling liquor illegally, but bootlegging by people outside the community is patronized by Lavallée upper and lower strata individuals. Often, during parties, when hard liquor supplies get short, a bootlegger will be called upon to save the situation. Among the wealthier families there are some who drink heavily and rather consistently. These people are criticized by others in the community ; a middle class person expressed the predominant feeling in this manner : "They are the leaders, and they shouldn't drink as much as they do. I know they can afford it, but they should not let their [121] drinking interfere with their work. Or, what is even worse, they should not let their drinking disrupt their family life." The poorer people who drink excessively are also criticized, perhaps more severely, because they cannot afford it.

Aside from these two forms of disapproved behavior, only very infrequent breaches of morality were observed or reported in Lavallée. For example there was mention of rare theft and of wife beating. So, while realizing the drinking and sexual acts which occur among them, Lavallée villagers speak with some pride about the high levels of morality found in their community-"the highest in the whole County," they say.

From our study of the County, it is our impression that the people of Lavallée are in the main right. They do stand very high in these matters, and if not at the top, they are close to it.

IV. PATTERNS OF RELIGIOUS LIFE

The central facts of religious life in Lavallée have already been implied in the preceding pages : depth and pervasiveness. We will now focus more specifically on religious institutions and practices.

It will be recalled that Lavallée is in St. Pierre parish, which contains the other shoreline communities of Philip's Point, Le Brun's Cove, St. Pierre, and a small backland hamlet, Frontière. The church building for the parish is one of the most impressive in this part of the Province. It is a large building, and made of stone in an area where all other churches are of wood. The building is an important Acadian religious center throughout the year, but it is particularly so during the festivities around August 15th which mark the feast day of the patron saint of the Acadians. At that time Acadians come from all over the Baie, Central Canada, and the United States.

In Lavallée, as in all St. Malo, the priest is expected to participate in many community affairs as well as in everything religious. All doors are open to him and, theoretically at least, all concerns are his. This orientation has a historical basis as well as an explicitly religious one, for during much of the last century the priest was the only person with education and he was needed in numerous matters of practical concern. Although today there are, of course, other people with considerable learning and knowledge, some of the tradition persists. The priest acts as an adviser or an active organizer in recreational, educational, [122] and sometimes even business affairs. We have mentioned that the Lavallée priest was instrumental in the development of the Credit Union and Cooperative. He also sits in on meetings of the St. Malo Board of Trade. The presence of the priest in nonreligious associations is considered by Lavallée people to be a contribution to the efficiency and smooth functioning of the organization. Although there are some private murmurings that have an anti-clerical tone, one hears no public statement to the effect that anything is outside the domain of his appropriate interest. It should be noted, however, that the position of the priest in Lavallée is to some extent the product of a particular individual's stature as a person and the picture is not altogether the same in other parishes.

The priest's activities are only one illustration of the influence of the church. The Lavallée people attribute to it the higher level of morality which they feel characterizes their village and they see religion as one of the most important of the bonds uniting the community.

In the FLS, 94 per cent of the respondents said that people of their village are either "all very religious" or "most very religious," which is considerably higher than the figure for the County as a whole (70 per cent). In terms of public religious participation, 34 per cent of the

TABLE III-7.

Scale of Public Religious Participation for Lavallée Household Heads

Compared to all Other Catholics in St. Malo (FLS)

|

Response Patterns

|

Lavallée

|

St. Malo catholics

Excluding Lavallée

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

(per cent]

|

(per cent]

|

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

34

|

17

|

|

-

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

60

|

73

|

|

-

|

-

|

+

|

+

|

6

|

5

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

5

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Total per cent

|

100

|

100

|

|

Weighted base for per cents

|

|

(1,299)

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

(33)

|

(203)

|

Key to columns

1 : attends meetings of church-sponsored organizations at least once a month.

2 : attends all or most of the religious services.

3 : attends church at least once a month.

4 : is affiliated with a church.

[123]

heads of households said they attend meetings of church-sponsored organizations at least once a month, as well as all or most of the religious services offered. As can be seen from Table III-7, this is double the figure for all other St. Malo Catholics. For details of the items in the scale, see Appendix B, pp. 481-482.

TABLE III-8.

Index of Private Religious Participation Among Lavallée

Household Heads Compared to all Other Catholics in St. Malo (FLS)

|

Private Religious Participation

|

|

St. Malo Catholics excluding Lavallée (%)

|

|

1. Says prayers and grace regularly or often and feels that religion is very important in his life.

|

|

|

|

2. Says either prayers or grace regularly or often and feels that religion is very important.

|

|

|

|

3. Says neither prayers nor grace regularly or often, but feels that religion is very important

|

|

|

|

4. Says either prayers or grace, or both, regularly or often, but feels that religion is only somewhat important

|

|

|

|

5. Says neither prayers nor grace regularly or often and feels that religion is only somewhat important

|

|

|

|

6. Says neither prayers nor grace regularly or often and feels that religion is of no importance

|

|

|

|

Total per cent

|

|

|

|

Weighted base for per cents

|

|

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

|

|

Whether outward religious behavior of this type is only on the surface, or whether it is an expression of deeply personalized religious sentiments is a question that may well be asked. In Lavallée, however, observation while living in the community and the results of key informant [124] interviewing leave us convinced that this behavior is not superficial.

Table III-8 shows the results of an attempt to make an FLS index of private religious participation. Lavallée and the rest of St. Malo are compared.

Considering the sample size, there is in this instance no essential difference between Lavallée and St. Malo generally. In all, three quarters of the heads of households feel that religion is very important in their lives and practice some form of home worship.

A questionnaire item which more indirectly bears on commitment to the religious community was : "If you had a friend who belonged to your denomination and he left, would you (a) feel less friendly toward him ; (b) stay friends, but try to get him to return ; or (c) consider it none of your business ?" Only 30 per cent of the Lavallée sample would consider it none of their business (compared to 38 per cent for St. Malo as a whole), while 70 per cent would take sterner measures. Of the latter, 14 per cent would break the relationship completely (compared to 15 per cent for the Municipality as a whole), and 56 per cent would try to get him to return (the comparable figure for St. Malo is 47 per cent).

A final survey item concerned intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants. Eighty-seven per cent of the Lavallée respondents "would object strongly" to one of their children marrying outside the faith, while the remainder would "object some." None of the respondents expressed themselves as having "no objection." Again, as in other features, one sees the heightening in Lavallée of some of the more widespread Acadian sentiments. The distribution for St. Malo as a whole is 70 per cent who would object strongly, 15 per cent who would object some, and 15 per cent who have no objections or say it "would depend on the other faith."

There is convergence, then, of the questionnaire indications with the anthropological field data on church participation and religious practices which points up the pervasiveness and intensity of community religious sentiments.

This evidence of high participation does not mean that there have been no changes in religious feeling and practice. Today in Lavallée it is said that religion is less collective and that some people are taking greater initiative in their ways of relating to God. This means, for example, less family worship, less emphasis on the family attending [125] church together, and the formation of age-defined cliques among the young people. In extreme cases there is increased importance attached to material "success" and even interest in birth control practices.

An attempt to show changes in religious participation is given in Table III-9 For details see Appendix B, pp. 485 ff.

TABLE III-9.

Index of Trends in Religious Involvement Among Household Heads in Lavallée,

other St. Malo Catholics, and the County (FLS)

|

Trend in Involvement

|

Lavallée

(%)

|

St. Malo Catholics excluding Lavallée

(%)

|

County

as a Whole

(%)

|

|

No decline : attendance at church as often or more often than before World War II, plus the statement that religion is as important or more important to the respondent than to his parent of the same sex.

|

76

|

80

|

56

|

|

Some decline : either attendance at church less often than before World War II or the statement that religion is less important to the respondent than to his parent of the same sex.

|

21

|

17

|

32

|

|

Large decline : both attendance at church less often than before World War II and the statement that religion is less important to the respondent than to his parent of the same sex.

|

3

|

3

|

12

|

|

Total per cent

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

|

Weighted base for per cents

|

|

(1,299)

|

(4,595)

|

|

Total number of interviews

|

(33)

|

(203)

|

(1,015)

|

Since both Lavallée and the St. Malo respondents are Catholic, comparison between these two units in terms of religious behavior is both meaningful and possible. Comparison with the County as a whole is more difficult, however, since here one half of the population is Protestant, which brings in consideration of factors of religious norms and expected practices. On the other hand, comparison of trends in [126] religious behavior, as in the above index, is probably justified-i.e., the evidence, within one broad religious division, of a greater trend toward secularization than is found in either Lavallée or St. Malo as a whole.

The discussion of religious life patterns in Lavallée has been brief. Reasons are easy to see, for in previous pages concerning the economy and community life patterns, aspects of the religion relevant for our purposes were so closely entwined as to make some anticipatory description of them necessary.

V. FAMILY LIFE PATTERNS

In Acadian culture the family in its religious context is still the most important basic social unit, regulating many economic, church-centered, and social activities. One expression of this in the past was the canton, a territorial division consisting of all members of one extended family. These cantons were an aspect of the pattern of dividing property equally among male descendants. In Lavallée today the canton no longer exists ; yet traditions and sentiments have been handed down which are its precipitates, and the village has strong cohesion based on kinship. Four large extended families are interlocked through marriage : the Lavallées, the Blanchets, the Guilbeaults, and the Campeaus. Of the total community population of 296, 281 individuals belong consanguineally and/or affinally to at least one of these four families. Thirty-two of the 281 belong to at least two of the extended families through an additional tie by marriage. Only five households (comprising fifteen people) have no consanguineal or affinal bond with the rest of the community. They consist of outside families who have moved in during recent times. And this absence of kinship linkage has some important social consequences for them. If, for instance, one of this group were to step out of line with the community's main sentiments, he would be more readily noticed and commented upon than would be the case if he were a member of one of the four family groups.